“It has always been science versus fundamentalism, not science versus religion.”

(Abhijit Naskar, Biopsy of Religions: Neuroanalysis Towards Universal Tolerance)

(Photo courtesy: http://www.businessinsider.com)

February 3, 2020: The luxury cruise ship Diamond Princess docked on Japanese shores and was promptly quarantined with 3711 people on board, because a passenger who had disembarked at Hong Kong two days earlier had tested positive for SARS-Cov-2, the Novel Corona virus causing COVID-19. Passengers & crew were either repatriated by their home countries or hospitalized in Japan over the next 4 weeks. Of them all, more than 700 were found to be infected with the virus. This was a unique opportunity – a Petri dish in a ship, if you may – for epidemiologists and virologists to study the disease and the virus.

At the beginning of this global pandemic, healthcare professionals and policy makers used data from the Diamond Princess experience and inferences thereof, such as infectivity & death rates, as a supplement to the observations from Wuhan to derive models of how the pandemic will play out in rest of the world. Later, after widespread devastation in Iran, Europe & the United States and after relative containment in Taiwan, South Korea & Singapore, experts have much larger datasets & a variety of scenarios to help develop disease prediction and control models.

So far, authorities in the Indian subcontinent appear to copy strategies of other countries to combat the pandemic. The curves of exponential ascendency of COVID-19 spread across countries appear identical, except in a few where healthcare response is more regimented. Yet, there are speculations about the survival of the virus in Indian climatic conditions, about Indians having a better innate resistance and about the impact of compulsory BCG vaccination in most Indians, that may have some effect on the expression of the disease in the country. Therefore, it may be worthwhile for India to study the actual transmission, clinical expression and outcomes of the disease in her own population and design responses to the pandemic based on these studies.

That is to say, we must find our own Diamond Princess before we find our Wuhan.

Indian government maintains that the COVID-19 pandemic has not reached Stage 3 in the country. Sceptics however, point at the shortened doubling rate and debunk the government’s position saying that community transmission of the SARS-Cov-2 has already begun. What is funny is that, even after knowing that India’s case trajectory is mirroring nearly every other country’s graph, the country – with people barely practicing adequate social distancing & violating lockdowns at their will – acts surprised that her COVID-19 numbers are rising! Prime time television is host to a raucous blame game: one set of people criticize the Government for a delayed initiation of lockdown & for poor organization of logistics; and another set of people hold reckless behavior by potentially infected individuals and groups as reason for rapid spread.

A singular event that has earned extraordinary ire from public & media as being the largest cluster of COVID-19 in India is the Tablighi Jamaat, as Islamic conference held in Nizamuddin Markaz, New Delhi in March. Following this congregation, there was a sudden upsurge in the number of COVID-19 positive cases in several states of India. Many states reported that, a major proportion of positive cases were delegates from the ‘Markaz’ congregation and their immediate contacts. Naturally, angry voices in the mainstream & social media were heard blaming the Tablighi, and implicitly the Muslim community for ‘un-flattening’ the COVID-19 curve. Some even accused Muslims of deliberately plotting to spread the disease in the country. That the Markaz delegates from some states refused to come forward for testing/quarantine as per Government advise, that Tik-Tok videos surfaced on how regular Namaz protects against Corona, and that healthcare workers trying to test the Markaz attendees were attacked in some places has not helped assuage this widespread suspicion.

Countering this blame are voices that criticize the establishment of selectively targeting the attendees for testing instead of making it more widespread. Their contention is that this lead to skewed statistics with disproportionate number of TJ cases. Fresh from the recent CAA protests, Muslims and their liberal supporters accused the Government and the right wing of aggravating the prevailing atmosphere of Islamophobia in the society.

In the midst of all this melee, what is overlooked is that the TJ congregation is a unique epidemiological opportunity for India to study the behavior of SARS CoV2 infection in the country.

Let me explain.

The events surrounding the TJ congregation at the Nizamuddin Markaz in March aren’t very clear. Some reports say that the event was inaugurated by 2nd-3rd of March and thousands of delegates, many from overseas attended the gatherings during the ensuing days in batches. The annual Ijtema was held between 13th & 15th of March and some 4500 to 8000 delegates (depending on which news you read) attended this event. On March 16th, the Delhi Government ordered that no more than 50 people can gather for any meetings including religious conventions. Following this, and until the intervention of India’s National Security Advisor on 28-29th March, more than 2300 delegates were sequestered at the Markaz, apparently not wearing masks and not strictly practicing social distancing norms. The evacuation of all these delegates from the mosque was accomplished only between 29th and 31st of March.

Now, this situation is somewhat akin to the Diamond Princess scenario. Markaz delegates were adult men of different age groups and presumably some were with comorbidities. Since it was a well-planned conference, the identity and contact detail of every delegate is known to the organizers. A bit of investigation into the proceedings of the conference can help understand the type of interaction/contact the delegates have had with the others.

For the moment, let us ignore the number of people each of the COVID Positive delegates managed to infect after the conference. Purely focussing on the cohort of primary delegates, we can study

- Rate of COVID-19-19 infections without social distancing

- Among those testing positive, how many are symptomatic & how many will be asymptomatic ‘spreaders’?

- What percentage will develop severe infections requiring hospitalisation

- What will be the death rate?

- What are the factors that predict severe infection and mortality?

Data generated by such a study can still give unique insights which can be used to plan the future of the pandemic in the country. Fundamentally we have to understand that: attending a legally permitted religious conference is no crime. Contracting a contagion in the Markaz is no different than contracting it in a Luxury Cruise ship. Stigmatising Markaz attendees or their contacts is only going to feed the divisiveness.

On the other hand, volunteering information about going to Tablighi Jamaat Markaz is no embarrassment or blasphemy. Getting tested and submitting to quarantine as needed is a moral obligation of the delegates to their loved ones & the society around

Because, scientific spirit must trump fundamentalism to protect human race.

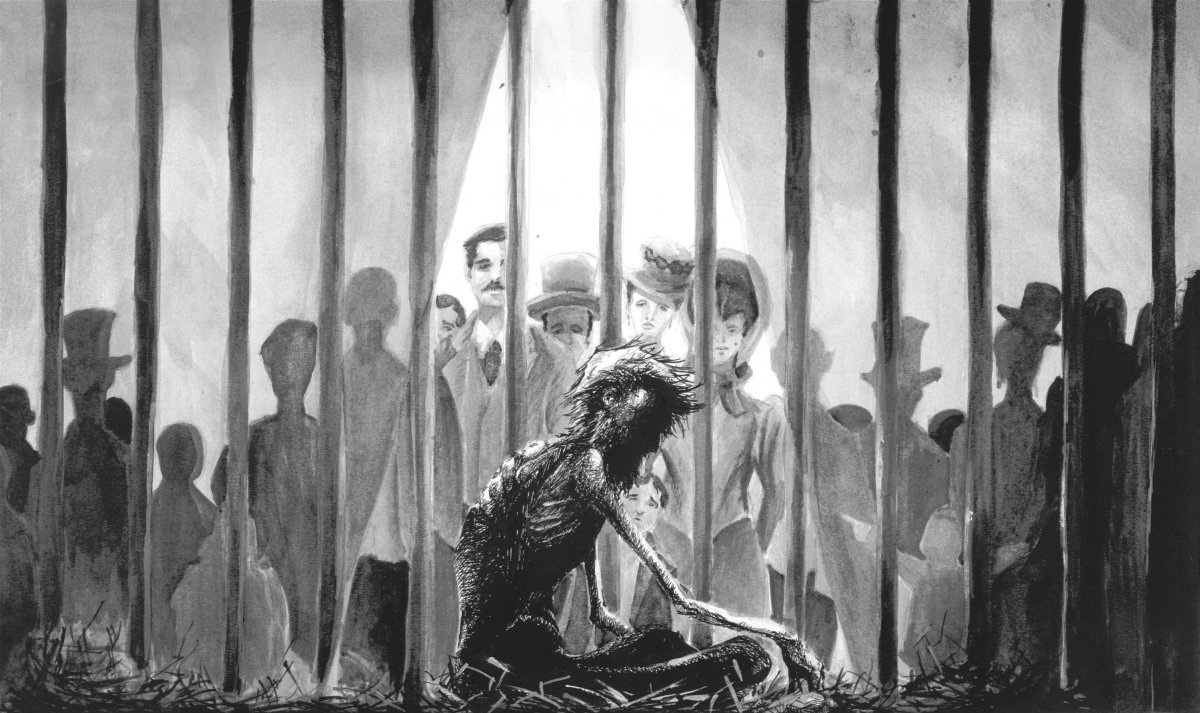

The questions, the insights, the metaphors in Franz Kafka’s short story, ‘A Hunger Artist’ are formidable.

The questions, the insights, the metaphors in Franz Kafka’s short story, ‘A Hunger Artist’ are formidable. Long post Alert, few spoilers

Long post Alert, few spoilers My review of Salman Rushdie’s ‘The Golden House’. (long post alert)

My review of Salman Rushdie’s ‘The Golden House’. (long post alert)